CONNECTING MEMORIES

More than 70 years after the end of World War II, I took my first trip to the Nazi extermination camps. It had taken me a few years to get to the point of needing to see the death camps with my own eyes. Even though my departure was in the evening, I had been stressed for days. The morning of the trip, I almost canceled. I was very scared. I took the day off and packed and unpacked my bags several times. Before I even got to the train station, I had already imagined the trip a number of times in my head.

Before I stepped onto the train at Amsterdam Central Station, I felt sick. Not because I was Jewish, I was not. I felt sick from reading about the crimes committed by the Nazi killing machines in thousands and thousands of concentration camps and death camps all around Europe, in nearly every occupied country, including the Netherlands.

A life story

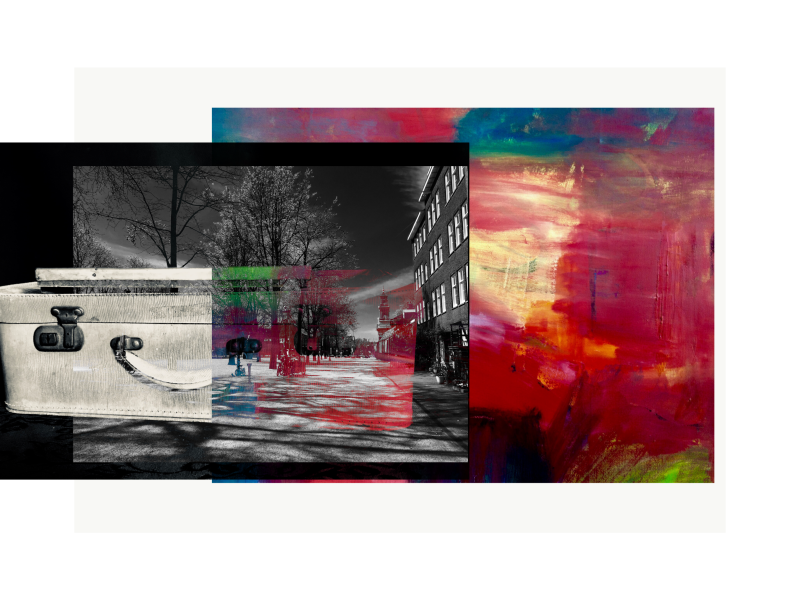

A life story Suitcase with candlesticks

Suitcase with candlesticks Suitcase with candlesticks

Suitcase with candlesticks Leaving

Leaving

Thinking of home

Thinking of home

Packing

Packing Suitcase

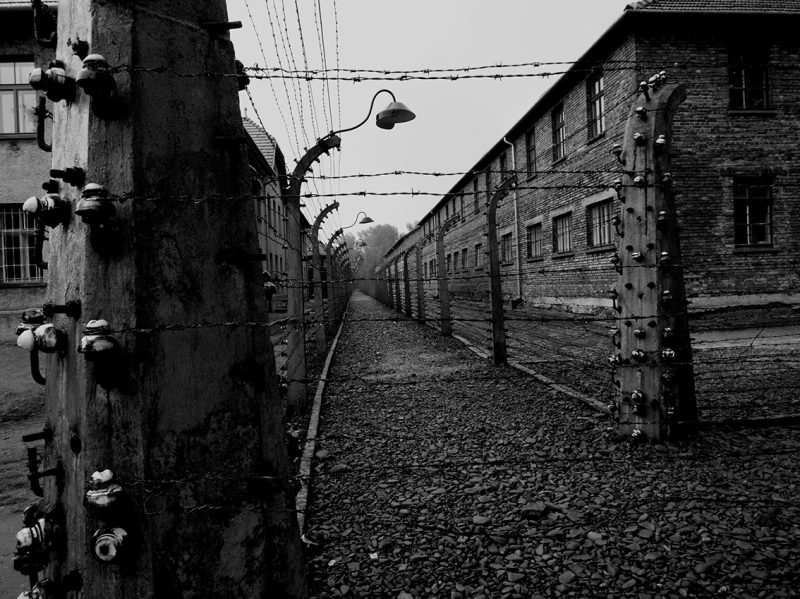

Suitcase Auschwitz

Auschwitz Arbeit Macht Frei -- Work Makes Free

Arbeit Macht Frei -- Work Makes Free Barbed wire

Barbed wire

"We were told to pack a suitcase"

"We were told to pack a suitcase"

Remembering Auschwitz

Remembering Auschwitz Halt! Danger!

Halt! Danger! Freight car at Auschwitz that was used to transport Jewish and Roma people to the death camp.

Freight car at Auschwitz that was used to transport Jewish and Roma people to the death camp. Identity

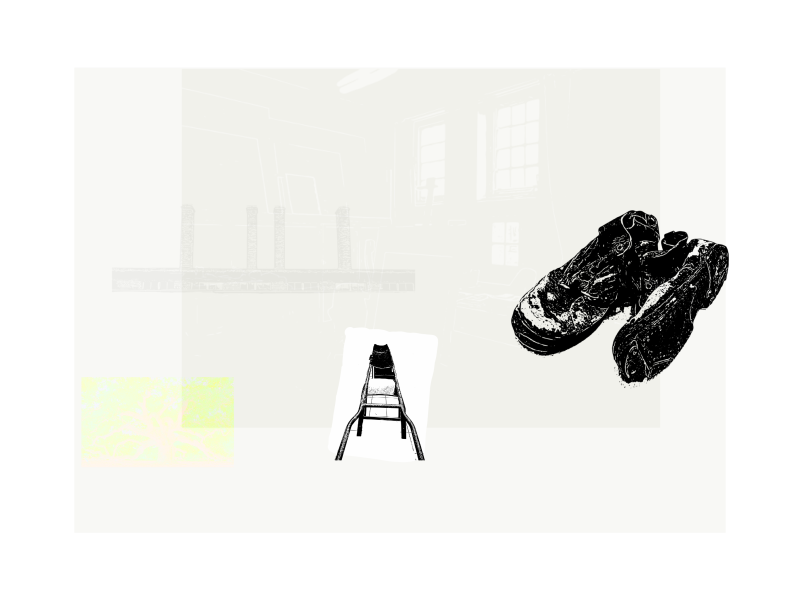

Identity Stretcher for transporting corpses

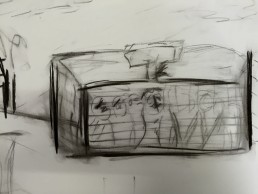

Stretcher for transporting corpses Train car in figure

Train car in figure Trees

Trees End of the line

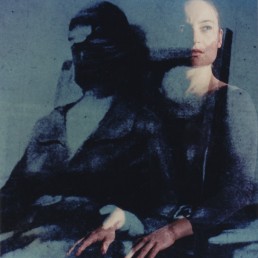

End of the line Figures with the buildings of the death camp superimposed on their bodies.

Figures with the buildings of the death camp superimposed on their bodies. Winged figure

Winged figure Figures

Figures

The train I was about to board would take me on nearly the same path as the 107,000 Dutch Jews3 were forced to take, not knowing most would never return. During the war, this train journey lasted for a minimum of three long days.

“On the third night the train suddenly stops. They have arrived at Auschwitz: blinding lights, barking dogs, screaming soldiers. The prisoners are beaten out of the train. On the platform the prisoners are separated: men to one side, women and children to the other.”1

During the trip, I found myself reflecting that I could never imagine, not even for a millisecond, that the land I called home would allow this horror to happen to their citizens simply because they were Jewish. Not even for a second, did I ever imagine anything that could compare to the horror that so many people had suffered. I later discovered even more unimaginable cruelty.

“[For] the extermination of Jews to occur, four principal things are necessary:

- The Nazis—that is the leadership, specifically Hitler—had to decide to undertake the extermination.

- They had to gain control over the Jews, namely over the territory in which they resided.

- They had to organize the extermination and devote to it sufficient resources.

- They had to induce a large number of people to carry out the killings.”2

***

For years after the first trip, I took trains to death camps, each new visit becoming more painful than the one before. The Holocaust is not only one of the most horrific acts in history, it is also one of the most sensitive subjects to try to capture in art, writing, or filmmaking. It is crucial to keep in mind the historical facts and inconceivable suffering and to navigate the thin line separating sentimentality from emotional honesty. It is important to avoid being emotionally misleading or incorrect or exploitative of the pain of victims. All of these considerations have been in my mind and have caused me a lot of uncertainty.

Most artists and people who love the arts have experienced something that awakens a surprising knowledge they didn’t know they had. Sometimes it’s music that transports you in time or to a place you’ve never been. Sometimes it’s a painting or a sculpture or a film. There is something in art that makes space for deep emotion and empathy. This is what I explore in this project and why I call it Connecting Memories. The project aims to open that space and to connect the past with the present and the future.

Pablo Picasso once said that painting is like keeping a diary. This is true of me. This work dealing with Europe’s shameful past during is a perfect example. The drawings, paintings, and photos in this book have become a way for me to release some of the horror and shock of learning the details of World War II and the genocide of so many Jewish, homosexual, and Roma people.

In the work, I am mixing the past and the present, imagining the uncertainty that marked the first roundups of Jews, and trying to gain insight and explore my own process of coming to terms with history. The images represent my own effort to understand and address what I was discovering.

“Memory is ceaselessly engaged in casting out one thing and putting something else in its place or superimposing new insight. The process is unending.”3

The work published in this book includes images made by me during trips to Auschwitz and other death camps, as well as work done in a studio setting, and mixed-media made with photos and drawings. In the mixed-media, only five of the photographs are taken from archives. All the others were taken by me.

[Editor's note: This essay is excerpted from the introduction to the book Connecting Memories.]

References

1) Deportations from The Netherlands www.HolocaustResearchProject.org: http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/nazioccupation/holland/netherdeports.html. "Overall, 107,000 Dutch Jews had been deported, of whom approximately 102,000 had perished. Probably another 2,000 had been killed, committed suicide or died of privation in Holland itself. The death toll represented almost 75% of the pre-war Jewish population, the highest proportion of Jewish fatalities for all of Nazi-occupied Western Europe. How could this have happened in a country renowned for its alleged tolerance and compassion?"

2) Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. Hitlers Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. New York: Knopf, 2002

3) "NOT I" Memoirs of a German Childhood. By Joachim Fest. Translated by Martin Chalmers. Illustrated. 427 pages.

Work in Progress

“I have seen that it is not man who is impotent in the struggle against evil, but the power of evil that is impotent in the struggle against man."

I visited Auschwitz for the first time in 2013.

I got on a train from Amsterdam to Warsaw and then took two more trains before arriving at the death camp.

I'd been reading about the Holocaust for several years by then, learning everything I could. And yet...I was not prepared for the emotions I would feel after that first visit. It was like I was one person before the visit and another after. Art is the only way I know to express the anguish of history.

Nearly every single day since I first took the train to Auschwitz, I have been drawing, painting, reading, and researching about the Holocaust. I have been told that there is nothing left to discover, that we learned the lesson of the Holocaust, that it's in the past, and that it is not your history, why should you care? And yet, discoveries keep coming, lessons continue to be unlearned, the past continues to affect the present, and I do care. I care very much.

I think often of the books I've read in trying to understand the Holocaust: Elie Wiesel's Night, Heydrich: The Face of Evil, The Kindly Ones, Rudolf Vrba's I Escaped Auschwitz, and many more. I think of the horror, the frustration, the disbelief, and finally, what Vassily Grossman describes as the "stupid kindness." In his book, Life and Fate, he writes:

I have seen that it is not man who is impotent in the struggle against evil, but the power of evil that is impotent in the struggle against man. The powerlessness of kindness, of senseless kindness, is the secret of its immortality. It can never by conquered. The more stupid, the more senseless, the more helpless it may seem, the vaster it is. Evil is impotent before it. The prophets, religious teachers, reformers, social and political leaders are impotent before it. This dumb, blind love is man’s meaning. Human history is not the battle of good struggling to overcome evil. It is a battle fought by a great evil, struggling to crush a small kernel of human kindness. But if what is human in human beings has not been destroyed even now, then evil will never conquer.”

― Vasily Grossman, Life and Fate

Work In Progress

The images in the slideshow below represent my current work in progress. These were all made in 2020 and 2021. If you are interested in the work, please contact me at [email protected].

Bystanders

Bystanders Red

Red Yellow Chaos

Yellow Chaos Red 2

Red 2

Dehumanizing

Dehumanizing Outside

Outside Figures

Figures Group in black and white

Group in black and white

Night

Night

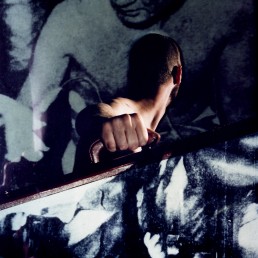

Despair or Rage or Both?

Despair or Rage or Both? Looking In

Looking In Rage and Despair

Rage and Despair Guard Dog

Guard Dog Despair Embodied

Despair Embodied

ABOUT STUPID KINDNESS

STUPID KINDNESS

Statement

“It is not always events that have touched us personally that affect us the most.”

― Elie Wiesel, Night

I was just old enough to become politically active during the time of the Shah. I was a teenager, born into a Muslim family, in the dusty capital of Iran’s Central Province. I was filled with a desire for justice and the conviction that ours could be a better society. In the first years after the Shah fell, it became clear that leftists and others were being targeted for torture, imprisonment, and execution. That’s when I fled the country, first to Pakistan and eventually to the Netherlands. The Netherlands became my new home and, almost immediately I came into contact with survivors of the Holocaust. They were my teachers and mentors. They were artists I respected.

I could feel something still haunting my new home. There was so much unspoken. As I struggled to understand my own country’s recent past and my new country’s culture, I found that I was turning to survivors of the Holocaust and the history of World War II for answers.

Stupid Kindness is a series of paintings and drawings inspired by research into the Holocaust.

The title is taken from Vassily Grossman’s book Life and Fate:

“This kindness, this stupid kindness, is what is most truly human in a human being. It is what sets man apart, the highest achievement of his soul. No, it says, life is not evil!”

As the years passed in Europe, I became more and more curious about the history of World War II and the Holocaust. I began reading everything hI could, from books by Elie Wiesel and Vassily Grossman to the more recent novel The Kindly Ones.

I began talking with experts and survivors. What I learned from this research took root in my imagination, forcing its way onto canvas in a series of paintings and drawings.

In these images there is anguish and horror, despair and hope, anger and survival. The landscape is on fire. The portraits are marked by terror, surrender, and exhaustion.

It sometimes feels as if the history of the Holocaust and the memories of its victims are a virus that have burned themselves into our very souls. As if their memories have become ours. As Elie Wiesel wrote:

“It is not always events that have touched us personally that affect us the most.”

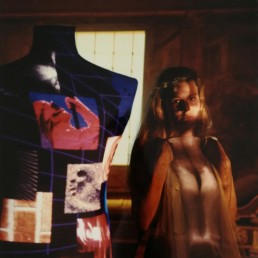

TRAVELER

Traveler

Now it feels like I was so fresh in Europe when I made these photos. My life in Iran was so close and so far. There was no internet. Phone calls were expensive. Really expensive. The war between Iran and Iraq was barely over. And Europe's past was unfolding around me. It was giving up its mysteries. I imagined a time traveler. Someone who saw the past, present, and future all at the same time. This time traveler saw Nazis in the streets, carried a suitcase filled with gangsters and ghosts, visited landscapes of comics and cold. At the time, I was a short 5-hour flight away from Tehran. But the trip was a time I could not, would not travel to. My time traveler, however, could make any trip.

CHADOR

My sisters grew up without forced hijab. In the Iran of their childhood, some women wore hijab. Some did not. Our mother always wore a headscarf. She kept a flowered chador by the door. She didn’t ask her daughters to wear the traditional Islamic dress. It was the State that asked them, that forced them into the veil. CHADOR is a project that represents my struggle understanding what happened to my sisters, to us, to Iran. In it, I examine my childhood memories, fact, fiction, and change.

Featured in Neuland Magazin No 10: Unveiling Iran (2010) and in Hollands Licht (2001).

CHADOR

CHADOR CHADOR

CHADOR CHADOR FLAG

CHADOR FLAG

CHADOR

CHADOR CHADOR

CHADOR CHADOR

CHADOR CHADOR

CHADOR CHADOR

CHADOR

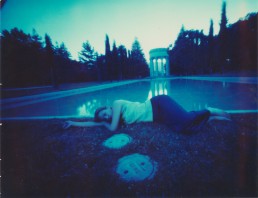

ANGELS

These images were made in the studio. There is no photoshopping or double and triple exposures. It’s all there in the studio: the water, the floating, the models.

I don’t know why I started this project. Was it simply the beauty of what was possible? What I could do with the camera? Was it a poem I read about Florida? So many things came together. I know these images contain violence and gentleness simultaneously. The angels might be drowning. They might be floating. They might even be swimming.

Underwater

Underwater Angels underwater

Angels underwater Floating

Floating Underwater

Underwater Angel

Angel Self-portrait as angel

Self-portrait as angel Cloaked

Cloaked Daring

Daring Two angels

Two angels Two cloaked

Two cloaked ANGELS (1992)

ANGELS (1992) Drowning

Drowning Drowning

Drowning

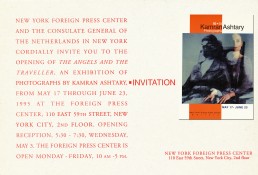

EXHIBITIONS

1987: One-person show, the International Student Club Gallery (LISC), Leiden, the Netherlands

1988: International group show, The Other Side of Photography, Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam

1991: Group show, The End of the Year Show, Houghton Gallery, New York City

1993: International invitational group show, De Wereld Van de Kunst, Hooglandeskerk, Leiden

1993: Group show, Waar Heen? Waar Voor?, Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam.

1993: Invitational Group Show, Select Work: Rietveld Acadamie, Het Veen Gallery, Amsterdam

1993: One-person show, The Other Side of New York, The US Foreign Press Center Gallery, New York City.

1994: Photographer for The Crown Heights History Project exhibition, Brooklyn Children’s Museum.

1994: One-person show, The Traveller, Gallery & Cafe Matisse, San Jose, California.

1995: Group Show, In Defense of Expression, San Jose Center for Latino Arts, San Jose, California.

1995: One-person show, The Traveller and the Angels, The US Foreign Press Center Gallery, New York City.

1995: Group show, Art Against Death, Puffin Room Gallery, New York City.

1996: Group show, Open, Kismet Gallery, San Jose, California.

1997: Group show, Works Gallery, San Jose, California.

1997: Annual auction show, Works Gallery, San Jose, California.

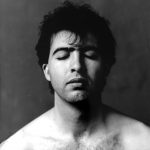

Bio

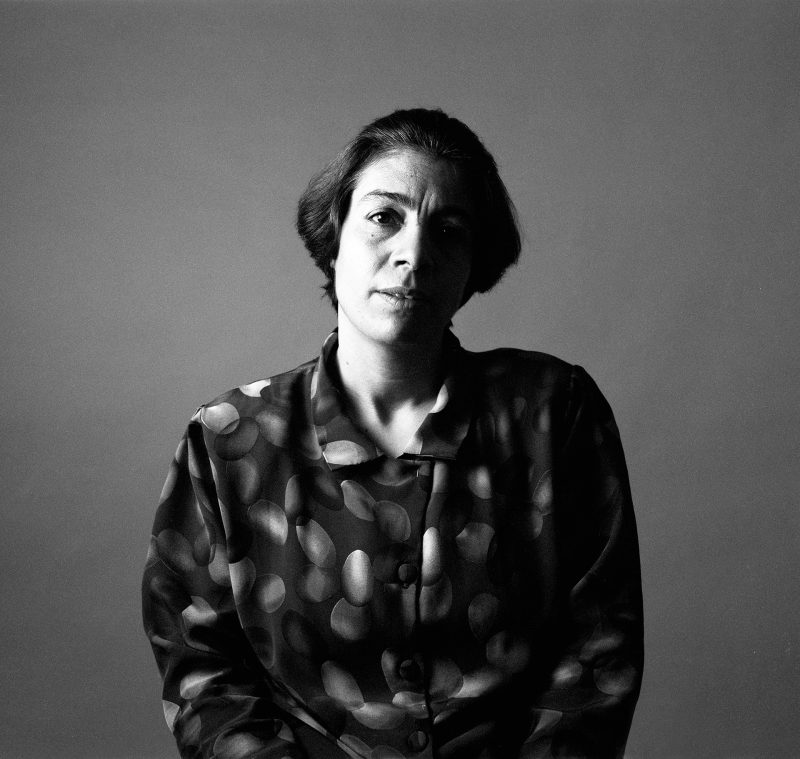

BIO

Kamran Ashtary is an artist, researcher, and human rights defender who lives and works in Amsterdam. Justice and the personal struggle with history as lived and as reported are at the heart of all of his work.

His art is influenced by those who mentored him when he was beginning to work and study as an artist: the artists Hans Haacke, Helly Oestricher, and Marlies Appel, and the philosopher Bert Taken.

Kamran was born in Arak, the dusty capital of Iran's Central Province. He was born into a Muslim family in Iran in the early 1960s. He came of age at a tumultuous time, when everything was in flux and revolution was coming. As a young teenager, Kamran became caught up in Iran's political upheavals. He was just old enough to be active during the time of the Shah and to participate in the revolution that toppled him. When it became clear that leftists and others in opposition to the new Islamist regime were being targeted for torture, imprisonment, and execution, Kamran fled the country. The Netherlands became his new home.

He became a citizen of the Netherlands where he graduated in art from the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. He also completed a one year scholarship at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York City.

After graduating from the Rietveld Academy, Kamran was invited by the New York Transit Museum to direct the Children’s Photography Project which he had co-founded two years earlier. Kamran led and organized two summer long photography workshops for children from Brooklyn's Gowanus housing projects. The project was featured on CNN and the Japanese news network NHK and was covered by multiple New York City newspapers. The children’s work was publicly exhibited to more than 100,000 people.

In 2006, to honor the 400th anniversary of Rembrandt’s birth, he was commissioned by Embassy of the Netherlands in Tehran to design and implement first exhibit of Rembrandt’s graphical work. After the success of the show, he designed the exhibit “Rembrandt & the Golden Age” exhibit which was hosted at the Saba culture center in Tehran The show was covered by the press in and outside Iran.

He has also been a member of several professional organizations and presented a number of lectures.

Currently Kamran is the executive director of Arseh Sevom, a civil society organization focused on Iran. He is frequently interviewed in the press about Iran and has given lectures on media in closed societies in Budapest, Athens, Berlin, New York, and Amsterdam. For several years he was also an invited speaker for Amnesty International’s Movies that Matter festival.

Since 2010, Kamran has spoken on human rights in secondary schools in the Netherlands as part of an Amnesty International effort.

Kamran's work has been published and exhibited all over the world. He is also the co-author of the photo book Iran: View from Here (2007) and editor and art director of the book Hope, Votes & Bullets (2009).

His work has been exhibited in the Netherlands, Iran, California, and New York and published in various books and magazines.