CONNECTING MEMORIES

More than 70 years after the end of World War II, I took my first trip to the Nazi extermination camps. It had taken me a few years to get to the point of needing to see the death camps with my own eyes. Even though my departure was in the evening, I had been stressed for days. The morning of the trip, I almost canceled. I was very scared. I took the day off and packed and unpacked my bags several times. Before I even got to the train station, I had already imagined the trip a number of times in my head.

Before I stepped onto the train at Amsterdam Central Station, I felt sick. Not because I was Jewish, I was not. I felt sick from reading about the crimes committed by the Nazi killing machines in thousands and thousands of concentration camps and death camps all around Europe, in nearly every occupied country, including the Netherlands.

A life story

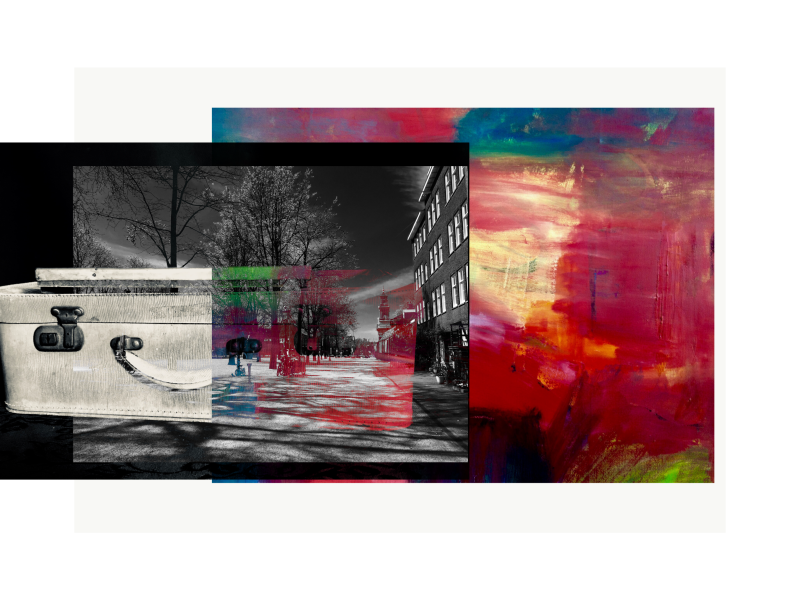

A life story Suitcase with candlesticks

Suitcase with candlesticks Suitcase with candlesticks

Suitcase with candlesticks Leaving

Leaving

Thinking of home

Thinking of home

Packing

Packing Suitcase

Suitcase Auschwitz

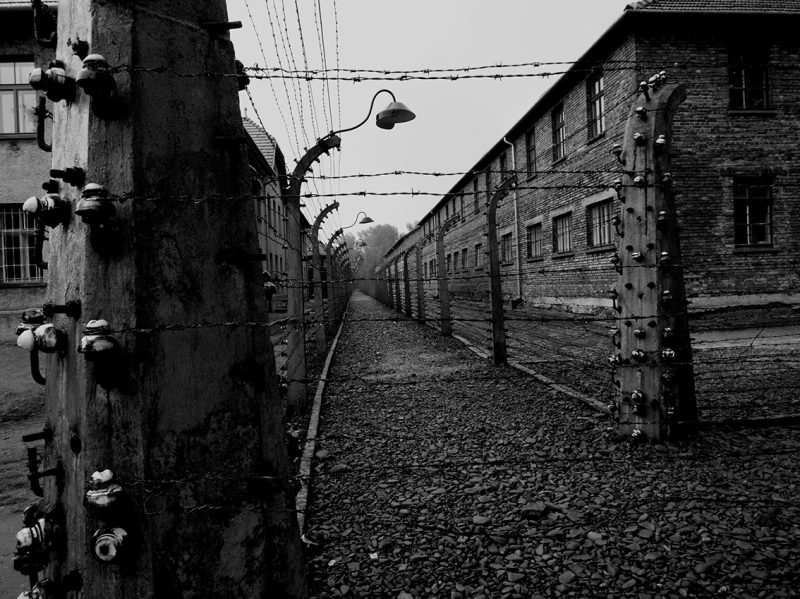

Auschwitz Arbeit Macht Frei -- Work Makes Free

Arbeit Macht Frei -- Work Makes Free Barbed wire

Barbed wire

"We were told to pack a suitcase"

"We were told to pack a suitcase"

Remembering Auschwitz

Remembering Auschwitz Halt! Danger!

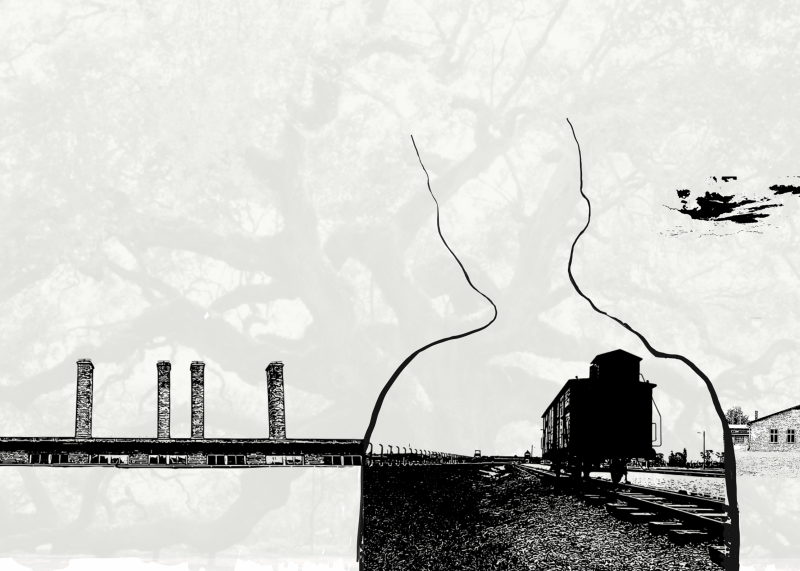

Halt! Danger! Freight car at Auschwitz that was used to transport Jewish and Roma people to the death camp.

Freight car at Auschwitz that was used to transport Jewish and Roma people to the death camp. Identity

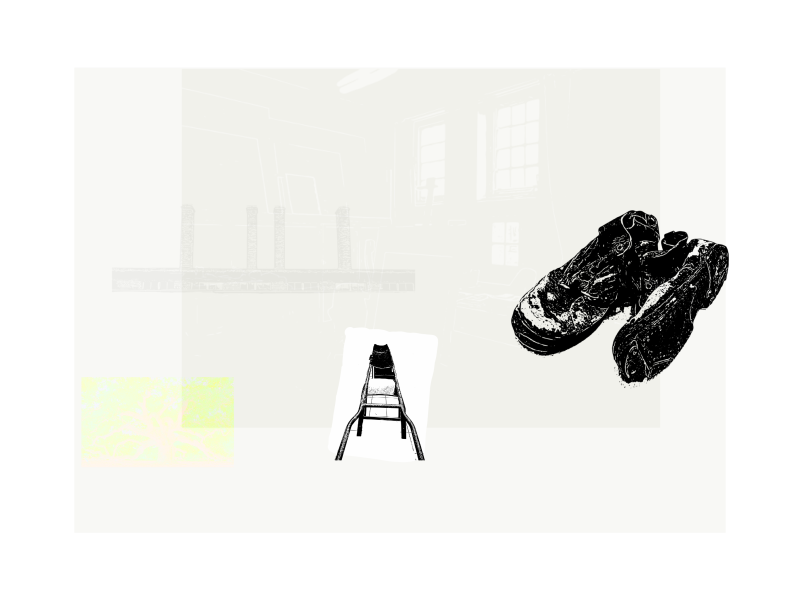

Identity Stretcher for transporting corpses

Stretcher for transporting corpses Train car in figure

Train car in figure Trees

Trees End of the line

End of the line Figures with the buildings of the death camp superimposed on their bodies.

Figures with the buildings of the death camp superimposed on their bodies. Winged figure

Winged figure Figures

Figures

The train I was about to board would take me on nearly the same path as the 107,000 Dutch Jews3 were forced to take, not knowing most would never return. During the war, this train journey lasted for a minimum of three long days.

“On the third night the train suddenly stops. They have arrived at Auschwitz: blinding lights, barking dogs, screaming soldiers. The prisoners are beaten out of the train. On the platform the prisoners are separated: men to one side, women and children to the other.”1

During the trip, I found myself reflecting that I could never imagine, not even for a millisecond, that the land I called home would allow this horror to happen to their citizens simply because they were Jewish. Not even for a second, did I ever imagine anything that could compare to the horror that so many people had suffered. I later discovered even more unimaginable cruelty.

“[For] the extermination of Jews to occur, four principal things are necessary:

- The Nazis—that is the leadership, specifically Hitler—had to decide to undertake the extermination.

- They had to gain control over the Jews, namely over the territory in which they resided.

- They had to organize the extermination and devote to it sufficient resources.

- They had to induce a large number of people to carry out the killings.”2

***

For years after the first trip, I took trains to death camps, each new visit becoming more painful than the one before. The Holocaust is not only one of the most horrific acts in history, it is also one of the most sensitive subjects to try to capture in art, writing, or filmmaking. It is crucial to keep in mind the historical facts and inconceivable suffering and to navigate the thin line separating sentimentality from emotional honesty. It is important to avoid being emotionally misleading or incorrect or exploitative of the pain of victims. All of these considerations have been in my mind and have caused me a lot of uncertainty.

Most artists and people who love the arts have experienced something that awakens a surprising knowledge they didn’t know they had. Sometimes it’s music that transports you in time or to a place you’ve never been. Sometimes it’s a painting or a sculpture or a film. There is something in art that makes space for deep emotion and empathy. This is what I explore in this project and why I call it Connecting Memories. The project aims to open that space and to connect the past with the present and the future.

Pablo Picasso once said that painting is like keeping a diary. This is true of me. This work dealing with Europe’s shameful past during is a perfect example. The drawings, paintings, and photos in this book have become a way for me to release some of the horror and shock of learning the details of World War II and the genocide of so many Jewish, homosexual, and Roma people.

In the work, I am mixing the past and the present, imagining the uncertainty that marked the first roundups of Jews, and trying to gain insight and explore my own process of coming to terms with history. The images represent my own effort to understand and address what I was discovering.

“Memory is ceaselessly engaged in casting out one thing and putting something else in its place or superimposing new insight. The process is unending.”3

The work published in this book includes images made by me during trips to Auschwitz and other death camps, as well as work done in a studio setting, and mixed-media made with photos and drawings. In the mixed-media, only five of the photographs are taken from archives. All the others were taken by me.

[Editor’s note: This essay is excerpted from the introduction to the book Connecting Memories.]

References

1) Deportations from The Netherlands www.HolocaustResearchProject.org: http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/nazioccupation/holland/netherdeports.html. “Overall, 107,000 Dutch Jews had been deported, of whom approximately 102,000 had perished. Probably another 2,000 had been killed, committed suicide or died of privation in Holland itself. The death toll represented almost 75% of the pre-war Jewish population, the highest proportion of Jewish fatalities for all of Nazi-occupied Western Europe. How could this have happened in a country renowned for its alleged tolerance and compassion?”

2) Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. Hitlers Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. New York: Knopf, 2002

3) “NOT I” Memoirs of a German Childhood. By Joachim Fest. Translated by Martin Chalmers. Illustrated. 427 pages.