Written for Hollands Licht, 2001

By Tori Egherman

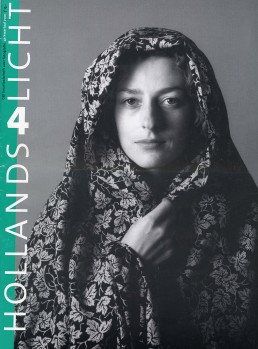

The chador is a single piece of fabric, usually, but not always, black. A woman drapes it over her head. It reaches her ankles. She may wear a headband to keep any stray hairs from escaping. One hand holds the chador closed. This leaves one hand free. Type chador into an Internet search engine, and you will get a host of responses that span human rights abuses, feminism, Islam, and instructions for making your own.Originally, perhaps, the chador protected a woman from bandits and rapists. It hid her body and her possessions. Walking quietly and carefully kept any possessions that she carried beneath the chador from making noises that would reveal them to others.

The chador in these photographs is blue with small white flowers. It is rarely worn outside the house, but instead hangs on a hook by the front door. A woman throws it on to answer a knock at the door. It is like a robe or housedress and not like street clothes. This type of chador is appropriate for Kamran’s photographs. The people in the photographs don’t normally wear chadors. For these photographs they quickly robed themselves with the chador. Once the photograph was taken, they took it off.

Kamran folds the chador like and American flag and photographs it. The chador is political. In some places, Iran in particular, the veil is required. The law makes personal choice irrelevant.

When I met Kamran’s sisters, who live in Iran, I was offended by the chador. Because they were forced to wear it by law and terror, I could not understand how or why any woman would choose to wear one. It seemed so much more powerful than a bolt of cloth. Then in Istanbul, I saw women dressed in long, silk, excruciatingly beautiful chadors. I saw a young woman dressed in faded overalls and a headscarf drinking tea with her boyfriend. I saw a woman in a black hijab with slits up the side, platform shoes, and fashionable black-rimmed sunglasses. I saw a woman in a faded hijab begging for money. I saw a three-year old play dress-up by wrapping a scarf around her dark, curly hair. The chador is personal. For some women it is a manifestation of faith. Yet, even where the veil is a matter of choice, it remains political. In Istanbul, where women are often punished for wearing a headscarf, the act of wearing a veil can be one of protest.

Many of the people in Kamran’s photographs are men. You can see in their faces that some of them are scared or nervous in a chador. One of the men actually looks happy with the veil.

Photographing men in veils is another way to photograph what is not there: the women who are required to veil themselves. Seeing men in veils helps us see the women more clearly. The photographs aim to erase the boundaries between women in veils and us.

The photographs in this series represent an effort to create images from a culture that resists, even forbids, representation. It is the struggle to create a representational imagery that interests me. When I say “representational,” I mean it in two senses: images that are figurative instead of abstract plus images that present an insider’s vision of a culture. The combination of the portraits with the objects evokes other images that are not explicitly shown: the women who wear chadors every day; memories of a life left behind; a world changing and changed.

When I look at these photographs, I am reminded of nights spent watching lunar eclipses. Looking directly at the moon during an eclipse makes it invisible. In order to see it, you have to look away. You have to look with the edge of your vision instead. The same advice applies to Kamran’s photographs. It is by indirection that you more clearly see both the women and the culture.

Writing this, I realize that it was not until 1996 that I ever spoke with a woman who wore a chador. That woman was Kamran’s mother. And she wasn’t wearing a chador when I met her: just a headscarf and modest dress. I flew from California to Amsterdam to meet her and two of Kamran’s sisters. Before we arrived, Kamran gave me a list of rules for meeting his mother: the one I remember most was “Don’t sit on the floor.” During the two weeks that we were together, Kamran’s mother broke all of the rules he set for me. Imagine my relief that she gave me permission to be myself and break her son’s rules.

Kamran has never seen his mother without a headscarf. For many reasons, she has always chosen to wear one. When I first met her, I was obsessed by the hair that was hidden under her scarf. Her ankles, feet, and wrists mesmerized me. I enjoyed sitting on the floor with her, drinking a small glass of tea, watching MTV, and stealing glances at her small, elegant feet.

View the series here: CHADOR